|

| A fact sheet that describes the CT scan procedure and technology and its uses in screening, diagnosis, and treatment. |

What is computed tomography?

Computed tomography (CT) is an imaging procedure that uses special x-ray equipment to create detailed pictures, or scans, of areas inside the body. It is sometimes called computerized tomography or computerized axial tomography (CAT).

The term tomography comes from the Greek words tomos (a cut, a slice, or a section) and graphein (to write or record). Each picture created during a CT procedure shows the organs, bones, and other tissues in a thin “slice” of the body. The entire series of pictures produced in CT is like a loaf of sliced bread—you can look at each slice individually (2-dimensional pictures), or you can look at the whole loaf (a 3-dimensional picture). Computer programs are used to create both types of pictures.

Modern CT machines take continuous pictures in a helical (or spiral) fashion rather than taking a series of pictures of individual slices of the body, as the original CT machines did. Helical CT (also called spiral CT) has several advantages over older CT techniques: it is faster, produces better quality 3-D pictures of areas inside the body, and may detect small abnormalities better.

In addition to its use in cancer, CT is widely used to help diagnose circulatory (blood) system diseases and conditions, such as coronary artery disease (atherosclerosis), blood vessel aneurysms, and blood clots; spinal conditions; kidney and bladder stones; abscesses; inflammatory diseases, such as ulcerative colitis and sinusitis; and injuries to the head, skeletal system, and internal organs. CT imaging is also used to detect abnormal brain function or deposits in adult patients with cognitive impairment who are being evaluated for Alzheimer’s disease and other causes of cognitive decline.

What can a person expect during a CT procedure?

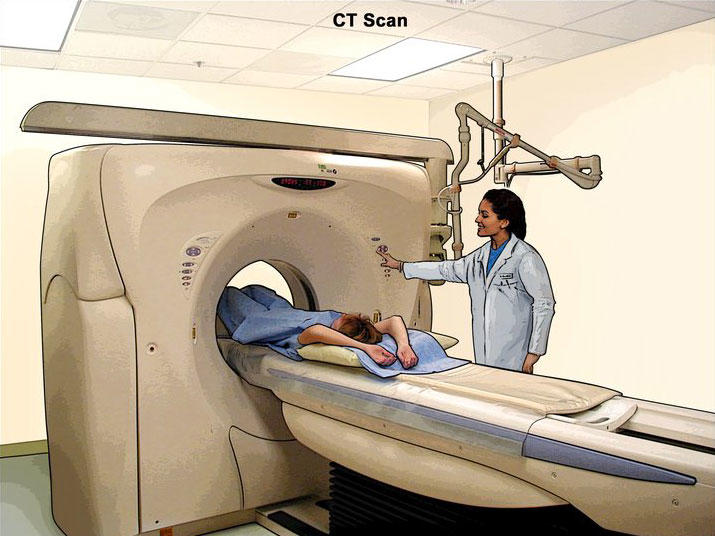

During a CT procedure, the person lies very still on a table, and the table passes slowly through the center of a large donut-shaped x-ray machine. With some types of CT scanners, the table stays still and the machine moves around the person. The person might hear whirring sounds during the procedure. At times during a CT procedure, the person may be asked to hold their breath to prevent blurring of the images.

Sometimes, CT involves the use of a contrast (imaging) agent, or dye. The dye may be given by mouth, injected into a vein, given by enema, or given in all three ways before the procedure. The contrast dye highlights specific areas inside the body, resulting in clearer pictures. Iodine and barium are two dyes commonly used in CT.

In very rare cases, the contrast agents used in CT can cause allergic reactions. Some people experience mild itching or hives (small bumps on the skin). Symptoms of a more serious allergic reaction include shortness of breath and swelling of the throat or other parts of the body. People should tell the technologist immediately if they experience any of these symptoms, so they can be treated promptly. Very rarely, the contrast agents used in CT can cause kidney problems for certain patients, such as those with impaired kidney function. Patient kidney function can be checked with a simple blood test before the contrast agent is injected.

CT is a noninvasive procedure and does not cause any pain. However, lying in one position during the procedure may be slightly uncomfortable. The length of a CT procedure depends on the size of the area being scanned, but it usually lasts only a few minutes to half an hour. For most people, the CT is performed on an outpatient basis at a hospital or a radiology center, without an overnight hospital stay.

Some people are concerned about experiencing claustrophobia during a CT procedure. However, most CT scanners surround only portions of the body, not the whole body. Therefore, people are not enclosed in a machine and are unlikely to feel claustrophobic.

Women should let their health care provider and the technologist know if there is any possibility that they are pregnant. Depending on the part of the body to be scanned, the provider may reduce the radiation dose or use an alternative imaging method. However, the level of radiation exposure in a CT scan is believed to be too low to harm a growing fetus.

Patient undergoing CT of the abdomen. Drawing shows the patient on a table that slides through the CT machine, which takes x-ray pictures of the inside of the body.

How is CT used in cancer?

CT is used in cancer in many different ways:

- To screen for cancer

- To help diagnose the presence of a tumor

- To provide information about the stage of a cancer

- To determine exactly where to perform (i.e., guide) a biopsy procedure

- To guide certain local treatments, such as cryotherapy, radiofrequency ablation, and the implantation of radioactive seeds

- To help plan external-beam radiation therapy or surgery

- To determine whether a cancer is responding to treatment

- To detect recurrence of a tumor

How is CT used in cancer screening?

Studies have shown that CT can be effective in both colorectal cancer screening (including screening for large polyps) and lung cancer screening.

Colorectal cancer

CT colonography (also known as virtual colonoscopy) can be used to screen for both large colorectal polyps and colorectal tumors. CT colonography uses the same dose of radiation that is used in standard CT of the abdomen and pelvis, which is about 10 millisieverts (mSv) (1). (By comparison, the estimated average annual dose received from natural sources of radiation is about 3 mSv.) As with standard colonoscopy, a thorough cleansing of the colon is performed before this test. During the examination, air or carbon dioxide is pumped into the colon to expand it for better viewing.

The National CT Colonography Trial, an NCI-sponsored clinical trial, found that the accuracy of CT colonography is similar to that of standard colonoscopy. CT colonography is less invasive than standard colonoscopy and has a lower risk of complications. However, if polyps or other abnormal growths are found on CT colonography, a standard colonoscopy is usually performed to remove them.

Whether CT colonography can help reduce the death rate from colorectal cancer is not yet known, and most insurance companies (and Medicare) do not currently reimburse the costs of this procedure. Also, because CT colonography can produce images of organs and tissues outside the colon, it is possible that noncolorectal abnormalities may be found. Some of these "extracolonic" findings will be serious, but many will not be, leading to unnecessary additional tests and surgeries.

Lung cancer

The NCI-sponsored National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) showed that people aged 55 to 74 years with a history of heavy smoking are 20% less likely to die from lung cancer if they are screened with low-dose helical CT than if they are screened with standard chest x-rays. (Previous studies had shown that screening with standard chest x-rays does not reduce the death rate from lung cancer.) The estimated amount of radiation in a low-dose helical CT procedure is 1.5 mSv (1). Those who have never smoked tobacco products are considered to be at too low a risk of lung cancer to benefit from lung cancer screening.

Despite the effectiveness of low-dose helical CT for lung cancer screening in heavy smokers, the NLST identified risks as well as benefits. For example, people screened with low-dose helical CT had a higher overall rate of false-positive results (that is, findings that appeared to be abnormal even though no cancer was present) than those screened with standard x-rays. NCI’s Patient and Physician Guide: National Lung Screening Trial provides more information on the benefits and harms.

The benefits of helical CT in screening for lung cancer may vary, depending on how similar someone is to the people who participated in the NLST. The benefits may also be greater for those with a higher lung cancer risk, and the harms may be more pronounced for those who have more medical problems (like heart or other lung disease), which could increase problems arising from biopsies and other surgery. However, because low-dose lung CT can produce images of organs and tissues outside the lung, it is possible that nonpulmonary abnormalities such as renal or thyroid masses may be found. As with extracolonic findings from CT colonography, some such findings will be serious, but many will not.

Under the Affordable Care Act, all Marketplace health plans, and many other health plans, must cover lung cancer screening with low-dose CT as a preventive care benefit for adults ages 55 to 80 years who have a 30 pack-year smoking history (e.g., smoked one pack of cigarettes per day for 30 years or two packs of cigarettes per day for 15 years) and are either a current smoker or a former smoker who quit within the last 15 years. People who think they might qualify for screening with low-dose helical CT should discuss the appropriateness and the benefits and risks of lung cancer screening with their doctors. They should also check with their health insurance company to determine whether this screening is covered by their insurance plan.

Medicare covers the costs of annual lung cancer screening with low-dose CT in beneficiaries considered to be at increased risk based on their smoking history. Annual screening is covered for Medicare beneficiaries who are between 55 and 77 years old; have no signs or symptoms of lung cancer; are either a current smoker or have quit smoking within the last 15 years; have smoked an average of one pack a day for 30 years (i.e., 30 pack years); and receive the screening and low-dose CT scan at a Medicare-approved radiology facility. Medicare coverage includes a prescreening counseling visit with the health professional who wrote the order to review the benefits and risks of lung cancer screening.

What is total, or whole-body, CT?

Total, or whole-body, CT creates pictures of nearly every area of the body—from the chin to below the hips. This procedure, which is used routinely in patients who already have cancer, can also be used in people who do not have any symptoms of disease. However, whole-body CT has not been shown to be an effective screening method for healthy people. Most abnormal findings from this procedure do not indicate a serious health problem, but the tests that must be done to follow up and rule out a problem can be expensive, inconvenient, and uncomfortable, and they may expose the patient to extra risks, such as from an invasive procedure like a biopsy that may be needed to evaluate the findings. In addition, whole-body CT can expose people to relatively large amounts of ionizing radiation—about 12 mSv, or four times the estimated average annual dose received from natural sources of radiation. Most doctors recommend against whole-body CT for people without any signs or symptoms of disease.

What is combined PET/CT?

Combined PET/CT uses two imaging methods, CT and positron emission tomography (PET), in one procedure. CT is done first to create anatomic pictures of the organs and structures in the body, and then PET is done to create pictures that provide functional data about the metabolic pathways (chemical reactions that take place in a cell to create and use energy) that are active in tissues or cells. Cancer cells often use different metabolic pathways than normal cells.

Patients undergoing a PET/CT procedure are administered a positron-emitting (radioactive) substance, or radiopharmaceutical, that is designed to target cancer cells specifically. Numerous radiopharmaceuticals have been developed. However, the most common PET procedure uses an imaging agent called FDG (a radioactive form of the sugar glucose). Because cancerous tumors usually metabolize glucose more rapidly than normal tissues, they take up more FDG and appear different from other tissues on a PET scan.

Other PET imaging agents can provide information about the level of oxygen in a particular tissue, the formation of new blood vessels, the presence of bone growth, whether tumor cells are actively dividing and growing, and whether cancer may have spread.

Combining CT and PET may provide a more complete picture of a tumor’s location and growth or spread than either test alone. The combined procedure may improve the ability to diagnose cancer, to determine how far a tumor has spread, to plan treatment, and to monitor response to treatment. Combined PET/CT may also reduce the number of additional imaging tests and other procedures a patient needs.

Is the radiation from CT harmful?

Some people may be concerned about the amount of radiation they receive during CT. CT imaging involves the use of x-rays, which are a form of ionizing radiation. Exposure to ionizing radiation is known to increase the risk of cancer. Standard x-ray procedures, such as routine chest x-rays and mammography, use relatively low levels of ionizing radiation. The radiation exposure from CT is higher than that from standard x-ray procedures, but the increase in cancer risk from one CT scan is still small. Not having the procedure can be much more risky than having it, especially if CT is being used to diagnose cancer or another serious condition in someone who has signs or symptoms of disease.

It is also important to note that everyone is exposed to some background level of naturally occurring ionizing radiation every day. The average person in the United States receives an estimated effective dose of about 3 millisieverts (mSv) per year from naturally occurring radioactive materials, such as radon and radiation from outer space (1). By comparison, the radiation exposure from one low-dose CT scan of the chest (1.5 mSv) is comparable to 6 months of natural background radiation, and a regular-dose CT scan of the chest (7 mSv) is comparable to 2 years of natural background radiation (1).

The widespread use of CT and other procedures that use ionizing radiation to create images of the body has raised concerns that even small increases in cancer risk could lead to large numbers of future cancers (2, 3). People who have CT procedures as children may be at higher risk because children are more sensitive to radiation and have a longer life expectancy than adults. Women are at a somewhat higher risk than men of developing cancer after receiving the same radiation exposures at the same ages (4).

People considering CT should talk with their doctors about whether the procedure is necessary for them and about its risks and benefits. Some organizations recommend that people keep a record of the imaging examinations they have received in case their doctors don’t have access to all of their health records. A sample form, called My Medical Imaging History, was developed by the Radiological Society of North America, the American College of Radiology, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. It includes questions to ask the doctor before undergoing any x-ray exam or treatment procedure.

What are the risks of CT scans for children?

Radiation exposure from CT scans affects adults and children differently. Children are considerably more sensitive to radiation than adults because of their growing bodies and the rapid pace at which the cells in their bodies divide. In addition, children have a longer life expectancy than adults, providing a larger window of opportunity for radiation-related cancers to develop (5).

Individuals who have had multiple CT scans before the age of 15 were found to have an increased risk of developing leukemia, brain tumors (6), and other cancers (7) in the decade following their first scan. However, the lifetime risk of cancer from a single CT scan was small—about one case of cancer for every 10,000 scans performed on children.

In talking with health care providers, three key questions that the parents can ask are: why is the test needed? Will the results change the treatment decisions? Is there an alternative test that doesn’t involve radiation? If the test is clinically justified, then the parents can be reassured that the benefits will outweigh the small long-term risks.

What is being done to reduce the level of radiation exposure from CT?

In response to concerns about the increased risk of cancer associated with CT and other imaging procedures that use ionizing radiation, several organizations and government agencies have developed guidelines and recommendations regarding the appropriate use of these procedures.

- The Image Gently campaign was launched in 2008 to raise awareness about methods to reduce radiation dose during pediatric medical imaging examinations. The campaign is an initiative of the Alliance for Radiation Safety in Pediatric Imaging, a coalition founded by the Society for Pediatric Radiology, the American Society of Radiologic Technologists, the American College of Radiology, and the American Association of Physicists in Medicine. The Image Gently website provides information about pediatric imaging for radiologic technologists, medical physicists, radiologists, pediatricians, and parents.

- In 2009, the American College of Radiology, the Radiological Society of North America, the American Society of Radiological Technologists, and the American Association of Physicists in Medicine created the Image Wisely campaign with the objective of lowering the amount of radiation used in medically necessary imaging studies and eliminating unnecessary procedures. The Image Wisely website provides resources and information to radiologists, medical physicists, other imaging practitioners, and patients.

- In 2010, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) launched the Initiative to Reduce Unnecessary Radiation Exposure from Medical Imaging. This initiative focuses on the safe use of medical imaging devices, informed decision-making about when to use specific imaging procedures, and increasing patients’ awareness of their radiation exposure. Key components of the initiative include avoiding repeat procedures, keeping doses as low as possible while maximizing image quality, and using imaging only when appropriate. The FDA also produced Reducing Radiation from Medical X-rays, a guide for consumers that includes information about the risks of medical x-rays, steps consumers can take to reduce radiation risks, and a table that shows the radiation dose of some common medical x-ray exams.

- The NIH Clinical Center requires that radiation dose exposures from CT and other imaging procedures be included in the electronic medical records of patients treated at the center (8). In addition, all imaging equipment purchased by NIH must provide data on exposure in a form that can be tracked and reported electronically. This patient protection policy is being adopted by other hospitals and imaging facilities.

- NCI’s website includes a guide for health care providers, Radiation Risks and Pediatric Computed Tomography (CT): A Guide for Health Care Providers. The guide addresses the value of CT as a diagnostic tool in children, unique considerations for radiation exposure in children, risks to children from radiation exposure, and measures to minimize exposure.

- The American College of Radiology (ACR) has developed the ACR Appropriateness Criteria®, evidence-based guidelines to help providers make appropriate imaging and treatment decisions for a number of clinical conditions. These guidelines and supporting documents are available on ACR’s website.

- ACR has also established the Dose Index Registry, which collects anonymized information related to dose indices for all CT exams at participating facilities. Data from the registry can be used to compare radiology facilities and to establish national benchmarks.

- CT scanner manufacturers are developing newer cameras and detector systems that can provide higher quality images at much lower radiation doses.

What is NCI doing to improve CT imaging?

Researchers funded by NCI are studying ways to improve the use of CT in cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment. NCI also conducts and sponsors clinical trials that are testing ways to improve CT or new uses of CT imaging technology. Some of these clinical trials are run by the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group, one of five groups in NCI’s National Clinical Trials Network. The American College of Radiology Imaging Network, which is now part of ECOG-ACRIN, performed the National CT Colonography Trial, which tested the use of CT for colorectal cancer screening, and participated in the NLST, which tested the use of CT for lung cancer screening in high-risk individuals

NCI’s Cancer Imaging Program (CIP), part of the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis (DCTD), funds cancer-related basic, translational, and clinical research in imaging sciences and technology. CIP supports the development of novel imaging agents for CT and other types of imaging procedures to help doctors better locate cancer cells in the body. In addition, CIP maintains the Cancer Imaging Archive, which is a library of medical images of cancer, including low-dose CT images, that are accessible for public download. This library has been used extensively by outside researchers in developing computer-aided diagnosis to help radiologists interpret CT images, for example, in lung cancer screening.

Where can people get more information about CT?

Additional information about CT imaging is available from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the federal agency that regulates food, drugs, medical devices, cosmetics, biologics, and radiation-emitting products.

Information about diagnostic radiology, including CT imaging, is also available at RadiologyInfo.org, the public information website of the Radiological Society of North America and the American College of Radiology.

Selected References

- American College of Radiology and Radiological Society of North America (April 2012). Patient Safety: Radiation Dose in X-Ray and CT Exams. Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- Berrington de González A, Mahesh M, Kim K-P, et al. Projected cancer risks from computed tomographic scans performed in the United States in 2007. Archives of Internal Medicine 2009; 169(22):2071–2077.[PubMed Abstract]

- Smith-Bindman R, Lipson J, Marcus R, et al. Radiation dose associated with common computed tomography examinations and the associated lifetime attributable risk of cancer. Archives of Internal Medicine 2009; 169(22):2078–2086.[PubMed Abstract]

- Committee to Assess Health Risks from Exposure to Low Levels of Ionizing Radiation, National Research Council. Health Risks from Exposure to Low Levels of Ionizing Radiation: BEIR VII—Phase 2. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2006.

- Frush DP, Donnelly LF, Rosen NS. Computed tomography and radiation risks: what pediatric health care providers should know. Pediatrics 2003; 112(4):951–957.[PubMed Abstract]

- Pearce MS, Salotti JA, Little MP, et al. Radiation exposure from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2012; 380(9840):499–505.[PubMed Abstract]

- Mathews JD, Forsythe AV, Brady Z, et al. Cancer risk in 680 000 people exposed to computed tomography scans in childhood or adolescence: data linkage study of 11 million Australians. British Medical Journal 2013 May 21; 346:f2360. doi:10.1136/bmj.f2360

- Neumann RD, Bluemke DA. Tracking radiation exposure from diagnostic imaging devices at the NIH. Journal of the American College of Radiology 2010; 7(2):87–89.[PubMed Abstract]

Posted:

Updated:

Reviewed:

Syndicated Content Details:

Source URL: https://www.cancer.gov/node/14686/syndication

Source Agency: National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Captured Date: 2013-12-04 15:00:03.0

Source URL: https://www.cancer.gov/node/14686/syndication

Source Agency: National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Captured Date: 2013-12-04 15:00:03.0

No comments